Experience Architecture is the most generalizable expression of creating an environment: it includes analysis techniques like usability and user-centered design, as well as instructional design and information architecture, findability and taxonomy. It is, perhaps, the name for one of the

Sciences of the Artificial that Herbert Simon wrote about in 1996.

Until recently, I had been satisfied that

Information Architecture would suffice to describe what I was talking about, but even though I had written about the process and products from a PTC (Professional and Technical Communication) perspective, database, information service, and information technology (IT) communities were still battling over its use, even if

Rosenfeld and Moreville had pretty much won on the intellectual merits of the case. When the usability practitioner community changed its name to the

User Experience Professionals Association, it became clear that merits be damned. There was change afoot.

Liza Potts, my colleague and friend, had been arguing for some time about the merits of using the title Experience Architecture for what we do. Her reasoning, which I have come to accept, is that as industry and practitioners flit about from term to term, from Usability to Information Architecture to User Experience Design to whatever may come next, that Experience Architecture is a reasonable term for this arena of the administrative arts and sciences of the artificial. Experience Architecture can be “ours" so long as the implied “we" is academe.

|

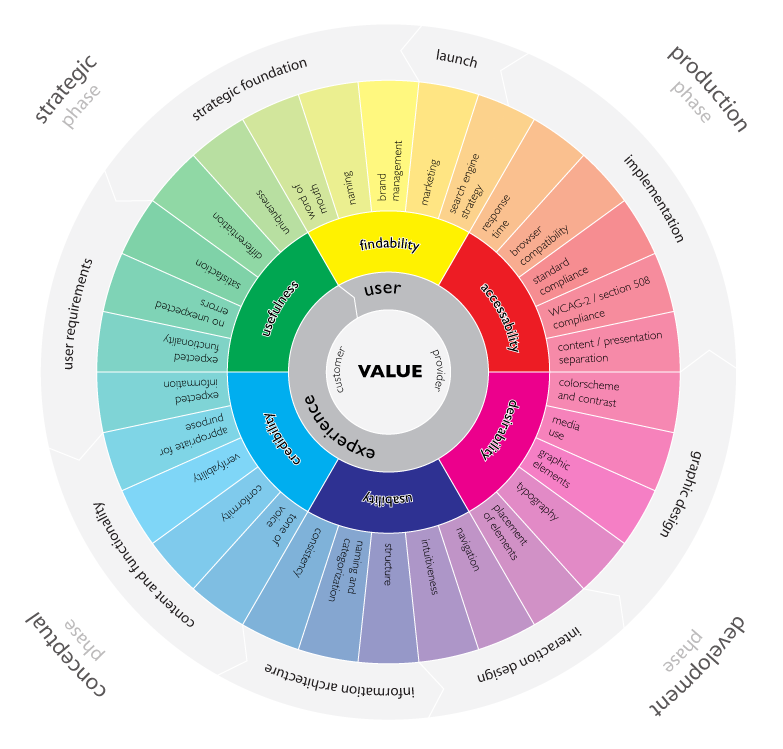

| Wheel graphic explaining value of User Experience Design. |

So many distinct subfields fit into this moniker Experience Architecture: information design, project management, document management, usability, user-centered design, document design, information architecture, findability, taxonomy: this isn’t a laundry list, at least not to me. These are places on a map, a map called UxD by practitioners and a map I’m learning to call Experience Architecture.

Every class is an experience waiting both the be experienced and designed. While the OWL Usability Project is a discrete experience, being designed to improve the Online Writing Lab’s online materials more accessible and more user-centered, the class in UxD is also designed to allow students majoring on professional writing to see themselves as future UX professionals. Or, if they do not want to go the route of digital design, to help them articulate their own focus within professional writing.

|

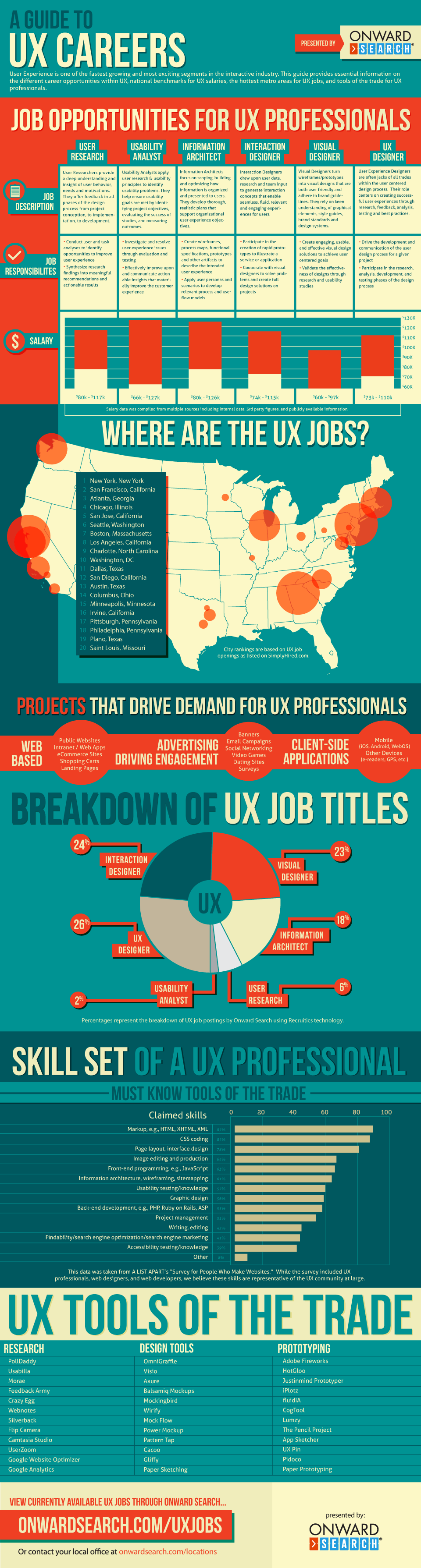

| A map of UX presented at UXThought.com |

I like to joke with the new majors that if I told them what career they would have at graduation I would be lying to them. Some don’t get it, while others look horrified. But I stand by my assessment: a recent graduate, who is now working for a major museum as their Social Media Coordinator, did what we later came to understand was an internship in social media. But in 2009, it was not clear what the field would be called nor what job titles would be instrumental in advancing the state of the art. Social Media Coordinator is now a thing, and it’s a title that programs and individuals are chasing. But you know what? The opportunities are now diminishing and there are more opportunities in other related as-yet unnamed pursuits.

It is that continuous and rewarding pursuit of the emergent, the new--what my colleague Patricia Sullivan have recently be calling the constant of change. That is what I am after. So it really does not matter if, in my class officially titled “Advanced Professional Writing,” we say we are studying UxD or Experience Architecture, or Social Media. What we are pursuing is the ever-emergent new, and articulating what’s next before it is yet articulated.

|

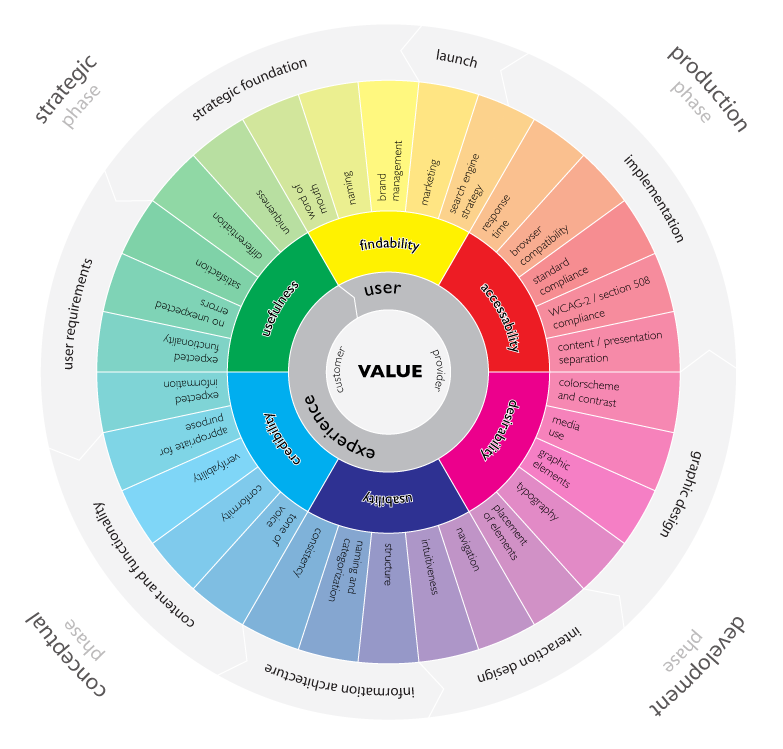

| Fred Cavazza's 2014 Social Media Map is an iterative design he updates annually. |

So we follow and lead: follow where people have made headway. Interestingly, we lead when we feel most lost. And this is what I have to constantly remind students, even those advanced expert graduate students, that when they feel most lost that they are making the best progress. When you are coining new knowledge, you have to feel like you are making it up. Because we are. emergent knowledge, the new, has to be disconcerting, uncanny, and uncertain precisely because its like has never been seen on the planet before, not in this guide, not in this context. And while many are quick to point out that nothing is new, and it’s all remix, all I’ll say is that, in a manner of speaking that is correct. Yet each new contextualization, re-contextualization, reappropriation, and rearticulation is something new that has not yet been experienced quite like this before.

This semester, I am teaching advanced professional writing, the capstone professional writing major class, as Rhetoric & Experience Architecture. Previously, I've taught it as UxD, Information Architecture, and Information Design. Each of these previous versions felt a little constrained, a little tight. The expansive nature of Rhetoric & Experience Architecture allows the class some breathing room: the technologically inclined students are running ahead of the pack with an

Eye Tracking Unit from Grinbath as well as a number of techno-gizmos, only to be added for user-centered functionality, of course. But there is a design team, a team dedicated to compiling an OWL style guide (which has been needed for years), as well as a real innovation I have been very happy to support. One mature student has taken on the role of project manager. Every class meeting, this student does the opening introduction to class, recapping what has been accomplished, upcoming deadlines, and what we said we would be doing in class for the day. At the end of class, the project manager recaps the day's accomplishments and forecasts deadlines and content for the next class. It hasn't displaced me as the classroom teacher but it has required me to renegotiate my pedagogy. In class the other day, the project manager led discussion while I took notes. I realized that not only hadn't I spoken for ten minutes, but that no students had turned around to look at me taking notes at the back of the class. That was a new and exciting development.

The class is, by definition, a site of instructional design. It is also a

designed user experience—an enactment of all the

core competencies at the heart of Technical and Professional Communication (TPC), and a safe space for inexperienced TPCs to try on a number of professional specialties at the start of their final year of study before joining practitioners in the field.

The goal for my class is to help students figure out how to maintain attention to and dedication for their role as user advocates. My goal for the OWL Usability Project is to continue to act as user advocate for the many worldwide millions of users of this wildly successful website that supports so many in their attempt to improve their written English skills. We aim to collect user data only to improve the site — building better experiences through understanding who is accessing existing resources, and through what technologies. We are seeking large numbers of responses to simple questions to see if the users we test more qualitatively represent our wide user base. We are also setting out to collect more metrics to accomplish similar goals. We aren’t interested in finding anything out about individual uses but rather in understanding the statistical probabilities of user patterns, to develop metrics so that we can better anticipate user needs. I invite you to volunteer if you have 5 minutes, 20 minutes, or 90 minutes to give to the OWL. Over the years, many of you have expressed interest in finding ways to give back to OWL, and this is your chance: we need your time, and we need anonymized data that only you can provide.

We know what text books look like from too many years of developing the genre, and we know what patterns of classroom instruction look like. And now, after 20 years, we know at the least what one OWL can look like. But what we don’t yet know is what the next 20 years of OWL might look like, we do not yet know what else is possible with the medium. It is possible that we have reached a dead end. It is also possible that over the next year or so of user inquiry and usability exploration that we might just get lost enough to realize that, in hindsight, we have invented whole new modes of engaging with the OWL’s users, new modes of providing content, and created whole new designs for interaction. That is, we may have just begun architecting the OWL users’ experience.

I hope you’ll join me and these energetic students in the project of inventing new possibilities for designing and sustaining the Online Writing Lab at Purdue.

|

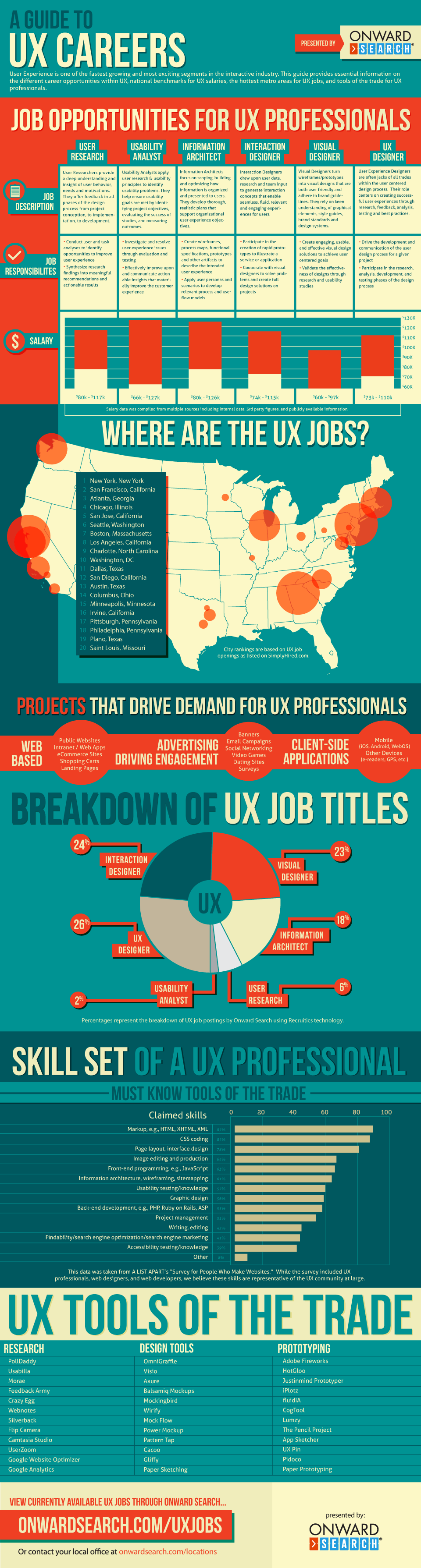

Taken from the UX Career Guide at Onward Search

http://www.onwardsearch.com/career-center/ux-careers-guide/ |